2 Million Dogs Are Stolen in the US Every Year—And It’s Causing Trauma

New study finds having a dog stolen feels like losing a child.

Share Article

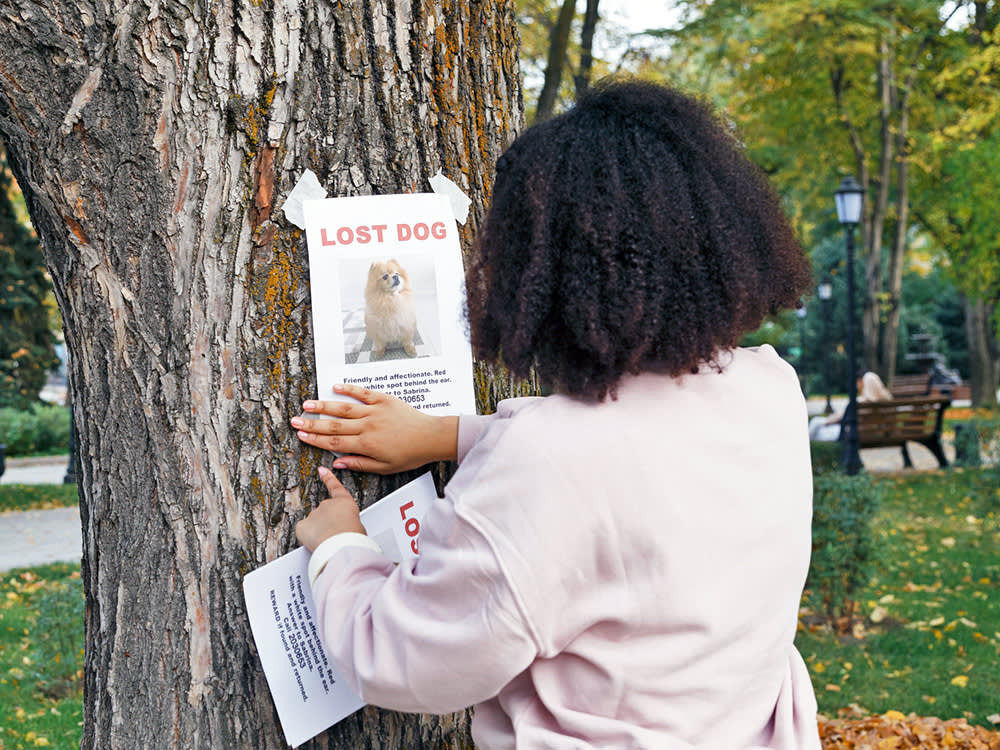

Dognapping might seem like a distant threat in the grand scheme of pet parenthood, but the phenomenon is more common than most might expect — and the emotional consequences for pet parents are devastating. According to the American Kennel Club, two million dogsopens in new tab are stolen in the United States each year — that’s nearly 200,000 thefts a month — and the problem is growing. In Los Angelesopens in new tab, especially, there have been increased instances of violent dog robberies.

Usually, stolen dogs aren’t kept as pets by the thief. “They’re either being sold or they’re being bred,” JoAnn Powell, co-founder of Dog Days Search and Rescueopens in new tab, a California nonprofit that helps owners find their lost pets, told us. “They know if [a dog] has not been altered they can breed it, or if it’s been altered, they know they can sell it at a higher price.”

Save on the litter with color-changing tech that helps you better care for your cat.

Designer dogs are at especially high risk, because thieves can sell them for thousands of dollars. French Bulldogs are the most commonly stolen dog breed; according to Tom Sharpopens in new tab, the CEO of American Kennel Club Reunite, twice as many French Bulldogs are stolen as the next most commonly stolen breed. Chihuahuas, Shih Tzus, Yorkshire Terriers, and Poodles are some other popular targets.

New research on the emotional impact of dognapping

A new study published in Human-Animal Interactionsopens in new tab explored the emotional devastation caused by pet theft. Four pet parents who had had their dogs stolen were interviewed for one hour each; each of these participants had been the primary caretaker of the dog and had lost the dog more than two months before the interview. The social media posts made by the pet parents on their accounts in the aftermath of the theft were also examined.

The researchers found that pet parents who were victims of dog theft experienced “emotional turmoil” that “equates that of missing loved ones, with additional complex experiences like disenfranchised grief and ambiguous loss,” wrote the study’s lead author, Akaanksha Venaktramanan.

Each of the participants referred to their lost dog as a family member. “‘They’ve (the dogs have) just always been our boys. We’ve got our girls. We’ve got two daughters, and our boys,” said one mother who was interviewed.

They all described experiencing extreme guilt as result of the dognapping; they searched relentlessly, experienced insomnia, and skipped work. The uncertainty was particularly emotionally difficult. “I go through phases of ‘He’s been stolen. No, he’s not. He’s dead in the woods. No, he’s been stolen. No, he’s dead,’ you know. And I wave it backwards and forwards,” one participant said. “I will never stop because not knowing is just horrific. This limbo is the worst… and I can’t stop until I have an answer,” said another.

The dognappings caused increased fear and vigilance, too. One participant installed CCTV cameras after her dog was stolen from private property. Another became terrified to leave her other pet alone for even a moment. “With [our new dog] […] I’m terrified […] I don’t want anybody to know we’ve got her. We’ve kept her really, really quiet,” said one interviewee.

Some of the people who experienced dognapping reported feeling a lack of understanding and support from their friends and family; they felt pressured to move on. This aligns with previous research, which has found that in cases when people experience dog theft, their social circles, including the police, opens in new tab often don’t take the situation seriously.

The study also found that social media was considered “safe and popular for expressing and processing complex emotion.” Participants found it therapeutic to “use words and pictures to process everything,” and social media facilitated search groups and connection. “The benefit participants experience from social media is immense, especially in managing their biggest priorities: the emotional turmoil and finding dogs,” Venaktramanan wrote.

Given the overlap between emotions surrounding dognapping and missing children, researchers believe victims of dognapping are at risk of developing PTSD. They hope future research can be dedicated to finding paths for therapeutic care and support resources for victims. Greater social and policy support is necessary, too, the researchers propose; at the moment, only 15 statesopens in new tab have laws specifically addressing dog theft — all other states treat dog theft as general theft of personal property.

Sio Hornbuckle

Sio Hornbuckle is a writer living in New York City with their cat, Toni Collette.

Related articles

![Golden retriever running around a local park during sunset]()

The Macro Benefits of Microchipping Your Dog

Sure, microchips can feel a little 1984. But if your pup has a chip, they’re four times more likely to make it home if they get lost.

![pet detectives and their dog on the trail looking for lost pets]()

Pet Detective: Improve the Odds When a Best Friend Goes Missing

Helping pet parents reunite with their lost pets.

![Woman sitting on the floor holding a white mixed breed dog in a relaxed living room setting]()

How to Choose a Trustworthy Dog Sitter

Leave your pup in the best possible hands with these tips.

![A woman with tattoos with close shaved blonde hair wearing a tan sweater hugging her merle coat dog outside of a dog shelter]()

Lost Pets: How to Get Them Back

Find out what to do when your pet goes missing with these tips from a pet recovery expert.

![Man hugging his fluffy white dog happily]()

Chemistry Between People and Dogs Is Real (It’s Science)

How the “love hormone” oxytocin connects us with our pups.