Do Dogs Actually Like Being Picked Up?

You want to hold them in your arms, but here’s how they really feel about being scooped up.

Share Article

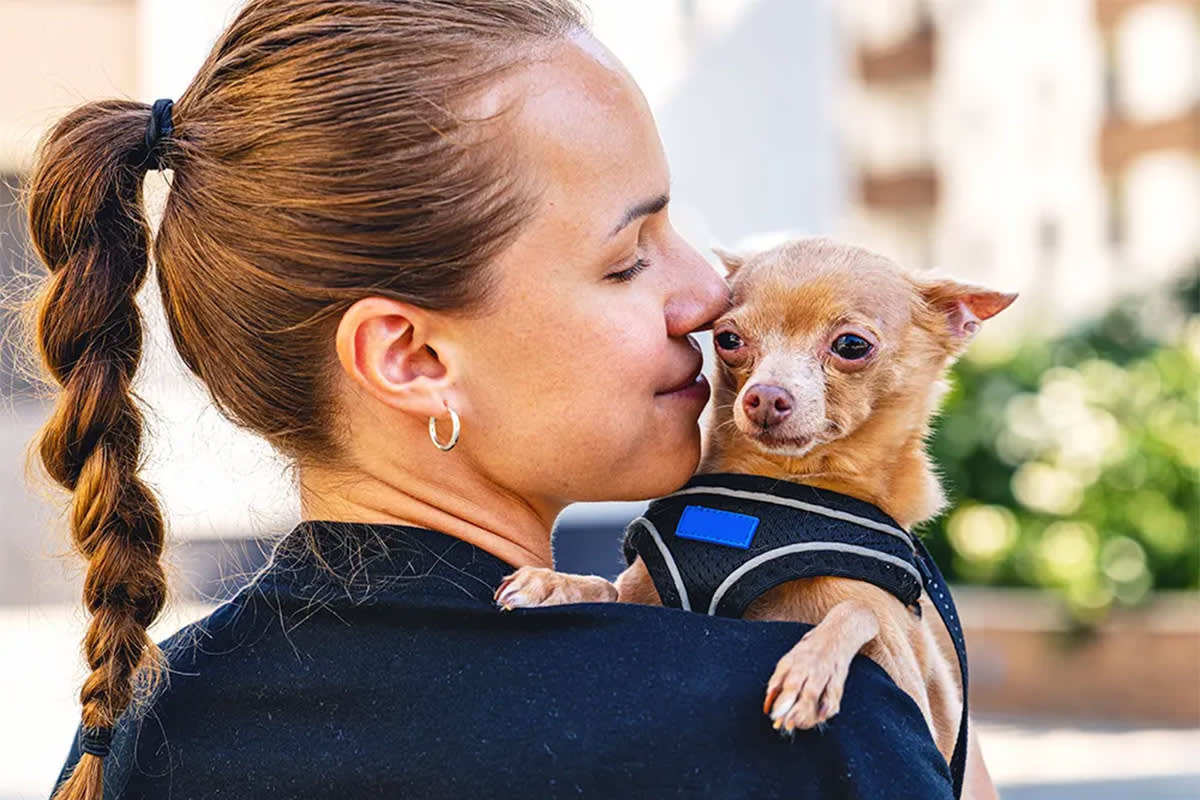

As a pet parent, it can feel completely natural to scoop your sweet dog into your arms for a quick hug, a little snuggle, or a trip down the stairs. But do dogs actually enjoy being picked up, or are they silently counting down the seconds until their paws are back on solid ground?

Whether your pup relaxes or resists might depend on their personality, past experiences, and what being held means to them (it isn’t always the same thing it means to us). To some dogs, being picked up can be a strange and stressful experience. So, how can you tell if your dog is actually comfortable with it? We talked to Dr. Carly Foxopens in new tab, senior veterinarian at Schwarzman Animal Medical Center and Dr. Eliza O’Callaghanopens in new tab, managing veterinarian at Small Door Vet, to help figure it out.

Your dog is probably communicating their comfort level to you already.

Dogs tend to be pretty clear about how they feel; you just have to know what to look for. As Dr. Fox explains, a dog who is comfortable being picked up won’t cry or stiffen. “They will often jump up into your arms and settle in or relax, rather than try to escape.” Dr. O’Callaghan adds that a comfortable dog “looks loose in the body, leans in, accepts your hands under the chest and rump, keeps soft eyes and a relaxed jaw, and may reorient to you once lifted.”

If your dog isn’t comfortable, their body language will show that, too. According to Dr. Fox, they may cry, stiffen, try to bite, or get away. Dr. O’Callaghan notes similar red flags: turning their head away, “whale eye” (seeing the whites of the eyes), lip-licking when no food is present, yawning, tense body, tucked tail, freezing, growling, or active struggling. “Those are all requests for space,” she says. “If you see any of them, stop and try another approach.”

Routinely picking up resistant dogs can be risky.

Consistently picking up a dog who doesn’t want to be held can lead to bad things for both of you. Dr. Fox warns that forcing a reluctant dog into your arms could result in injury to yourself or the dog, and it can lead to unwanted behaviors, like aggression or anxiety around people. She adds that lifting a dog who’s uncomfortable “should be done slowly and seriously, with a plan in place.” The key, she says, is patience: “You need to build trust, which takes time and dedication.”

Dr. O’Callaghan agrees, noting that ignoring a dog’s signals can have lasting effects. “Repeatedly overriding clear ‘no thanks’ signals can condition anxiety, avoidance, or defensive aggression, and it can erode trust in the relationship,” she says.

There’s also a physical concern: “A struggling dog is at higher risk of being dropped or of injuring the handler.” To prevent that, she recommends “reward-based handling and low-stress techniques” to help dogs feel secure and safe when they do need to be lifted.

Don’t assume all small dogs want to be picked up.

Small dogs are sentient individuals, too; they have thoughts, feelings, and preferences like any other dog. But it’s true that smaller dogs often become more accustomed to being held simply because it’s easier for people to pick them up and support their bodies properly. “Smaller dogs just acclimate to getting picked up, whereas larger dogs — it’s not a common occurrence for them, and they may act surprised or be generally uncomfortable with the process,” Dr. Fox says.

Dr. O’Callaghan, however, notes that a dog’s comfort with being held has more to do with trust and experience than with size. “What matters is who is doing the picking up, how predictable the handling is, and the dog’s learning history with that person. If your pup loves it when you pick her up, that is largely about trust, clear patterns, and a positive association with you. The same dog may squirm or avoid a stranger because there is no established routine, no consent cue, and the handling feels uncertain.”

She adds that dogs are most comfortable being lifted by people they trust, and by movement that feels predictable and supportive. A dog who’s been grabbed too quickly or lifted without proper support may associate being picked up with discomfort, especially around unfamiliar people or in stressful situations, like at the vet. Dr. O’Callaghan also points out that people tend to pick up small dogs more often simply because they can, so we notice more about their reactions — both good and bad. “Many large dogs would probably enjoy a short, supported lift onto the couch with their person,” she says, “but we tend to use ramps or invitations [for them to jump up on their own] instead.”

A dog’s comfort level being picked up can be formed early in life.

A dog’s attitude toward being picked up can trace back to their puppyhood. Dr. Fox notes that research supports this connection. “There is a critical socialization period (three to 14 weeks of life) where handling and socialization practices impact how the dog behaves later in life when being picked up, touched, or handled.”

Dr. O’Callaghan adds that those early interactions can make a lasting difference. Puppies who experience gentle, predictable handling during that window are more likely to feel comfortable with touch as adults. “Early, positive exposures to being held, examined, and having paws, ears, and mouths handled reduce fear and restraint stress as adults,” she says.

Small steps and positive reinforcement can help dogs gain comfort with being picked up.

Still, comfort with handling isn’t fixed in puppyhood. Helping a dog feel more comfortable being picked up, Dr. Fox says, “just takes slow desensitization and positive reinforcement.” Building trust and creating positive associations over time can help a hesitant dog feel safer with the experience.

Dr. O’Callaghan agrees, emphasizing that progress starts with respecting a dog’s boundaries. “Respect the communication in the moment, then train confidence,” she says. She recommends developing a predictable lifting routine by using a consistent cue, approaching slowly, supporting under the chest and hind end, and rewarding right after the dog is set down.

By pairing small steps with treats — and, crucially, giving your dog choice in the process — many dogs “become neutral or even happy about being lifted when they learn the pattern and trust the handler.” And if a dog still doesn’t love it, she adds, there’s no harm in finding alternatives like ramps, stairs, or encouraging them to jump onto a low surface instead.

Kelly Conaboy

Kelly Conaboy is a writer and author whose work has been featured in New York Magazine, The New York Times, and The Atlantic. Her first book, The Particulars of Peter, is about her very particular dog, Peter. (Peter works primarily as a poet.)

Related articles

![Cute black dog listening outside.]()

Are There Certain Sounds That ‘Attract’ Cats and Dogs? The Internet Thinks So

TikTok is full of videos that claim to show us how to speak to to our pets.

![Woman hugging her dog.]()

Most Dogs Don’t Really Like Being Hugged, New Study Finds

Yeah, it’s kind of heartbreaking, but your loving embrace might be stressing your pup out.

![A woman holding her dog close.]()

FYI, Your Dog Can’t Stand When You Do These 7 Things

Thanks, they hate it.

![Woman meditating with her chocolate lab in the living room.]()

Why You Should Do Breathwork With Your Dog—Really

It might sound woo-woo, but it can benefit you both.

![Man on the couch with his dog.]()

12 Things Your Dog Wishes They Could Ask You For

Tell me what you want, what you really, really want.